Before the question you are familiar with—or if this is your first letter, the one I trust you will grow fond of—Happy New Year. It’s good to be here with you.

Answer truly, if only for a moment and to yourself: how are you in the home of your body?

In considering the words that my home rests on since I have written to you, I am left with little but oscillating to describe my state. I have returned to earlier drafts of this segment to replace a word with another I find more apt, and in that way, the hands of time tick between expressions until this snapshot where the clock is stilled, the pendulum frozen. Frozen, until the home takes on a different shade or structure in response to the question’s renewal.

On Cocaine

XVIII

Because I had to be on a cocktail of glucose and other less exciting substances during the holidays, it became a running joke between my sister and me that I would recover quicker if I simply snorted the snow or rubbed it against my teeth—to ascertain the purity—instead of dissolving it in bottles and cups of water. Because this is a good idea—with roots in inter-house sports culture—we would dust our fingers with snow, after my cocktail, and rub the sweet dust into our teeth, throwing our heads back, feigning a high.

I promise this letter is not about cocaine.

Not at all.

Or not entirely.

Maybe just a bit.

After all, you are reading this line by line.

XIX

In his book of lectures and essays on poetry and writing, The Triggering Town, Richard Hugo makes an interesting distinction between a poem’s—or by extension, a work of writing’s—initiating or triggering subject and its real or generated subject. The former is what causes the poem and the latter is what the poem realizes—a feat achievable only during the writing.

This thought influences various writing aspects, one of which is how one considers what writing is about. As such, in line with Hugo’s triggering and real subject; Mary Ruefle refers to the theme of her essay On Theme as theme, but her real theme is poetry whose theme is mutability, while Chris Abani in a conversation, considered poetry as distilled beauty and the distilling language forms its subject, its primary impulse, making every other subject or interest secondary.

Thinking this way is as vital in developing craft as it is in developing self—recognizing intents, mind states and feelings for instance. Craft-wise, I realized recently that while the impulse to curate conversations that unwrapped like presents is true of these letters, perhaps what I was trying to realize was trust in my thoughts. In the time you have spent reading these letters you have glimpsed—for better for worse—how my mind makes associations. Perhaps I wanted a space for that. A space to watch those thoughts happen repeatedly and by that very repetition, develop a trust in them.

Self-wise, with enough introspection, one begins to realize things are hardly as they seem. Natalie Diaz refers to anger as a demand for love. Other literature has described anger as fear. James Baldwin considers White self-loathing masked in racism. George Saunders refers to worry as a form of care. José Olivarez considers how a lack of self-compassion guises as rigour. Herbsaint Sazerac—of The French Dispatch—declares all grand beauties withhold their deepest secrets. Dr Mardy Nichols—of Euphoria’s F*ck Anyone Who's Not a Sea Blob episode—described self-criticism as a cage while Jules considered it a compass, an anchor. Nigerian mothers offer meals as apology.

Perception. Appearance. Reality. Old problems.

XX

“Just as you must assume everything you put down belongs because you put it there (just to get it down at all) you must also assume that because you put it there it is wrong and must be examined. Not a healthy process, I suppose! But isn’t it better to use your inability to accept yourself to creative advantage? Feelings of worthlessness can give birth to the toughest and most welcome critic within.”

—Richard Hugo, Statements of Faith.

“When I first started writing, I hated myself for being so uncertain, about images, clauses, ideas, even the pen or journal I used. Everything I wrote began with maybe and perhaps and ended with I think or I believe. But my doubt is everywhere, Ma. Even when I know something to be true as bone I fear the knowledge will dissolve, will not, despite my writing it, stay real.

—Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.

As my mind moved through the world of a story I began imagining late last year, I made an interesting observation. I decided, among other things, to narrate the story from a third-person point of view—partly to accommodate the cast of characters and attempt a semblance of objectivity in narration—only to realize how unfamiliar it felt. The unfamiliarity was amplified by time, as my last narration using this view was a novel manuscript from five years ago.

Which begs the question why?

Of the narrative point-of-views, the third-person has the most objectivity associated with it. Along with that objectivity comes certainty, and while I saw the decision to write in that voice through and completed the draft, it became clear the reason the narrative voice felt unfamiliar was the certainty it presumed and required. I am certain of little and my doubt spares nothing, especially myself. Yet, the third-person narrative in its omniscience does not leave much room for uncertainty, for the unreliability of the narrator—except for the third-person limited narrative which offers a more intimate narration and with that more possibilities.

“[…] in our group text, Basma says I grieve most for our younger selves.”

—Safia Elhillo, Geneva.

When thinking of earlier versions of myself in this light, my impulse is to consider how my growing uncertainty has dwindled my confidence over the years. Yet—at the risk of making a case for those earlier versions—I doubt that impulse. I am aware of my predisposition to nostalgia and for all its honeyed recollection it is often dishonest. If I even concede that what those earlier selves had was confidence, it was an adolescent one, not only because of the period it blossomed in but because of what fostered it. Anyone can be confident in themselves, in their work, when that confidence runs its entire course unopposed.

In this way, much of adulthood becomes an immersion in moral dilemmas. You learn and develop various traits, virtues, values or beliefs, then you arrive at adulthood and find them being resisted by reality and circumstance. It is tempting in the midst of these dilemmas to long for the younger self, the one whose confidence was untested by failure, whose love was untainted by loss. Yet, I believe the adults we become, whether by retaining old values despite resistance or by developing new ones to adapt to reality are in service to resolving this dilemma—for better for worse. As such, while another conversation can be had about the nature of holding on to old beliefs for the sake of their familiarity; where an adult self retains an adolescent trait, such traits are refined by the resistance they survive—the way an idea is refined by its execution.

“And so Socrates concluded that what the oracle at Delphi meant was not that Socrates was wise but that at least he knew he knew nothing.”

—Mary Ruefle, Short Lecture on Socrates, Twenty-Two Short Lectures.

Another instance of that moral dilemma is the acknowledgement of paradoxes. In the face of dilemmas, developing an acceptance for multiple truths coexisting is vital. It is such an acceptance that Simone de Beauvoir writes towards in her text The Ethics of Ambiguity where she acknowledges man as both subject and object, both freedom and facticity. This acceptance allows the value of traditional vices to be recognized. As such, while Dr Mardy Nichols makes a healthy, valid point in her question to Jules, I am inclined to agree with Jules. To imagine a self void of criticism, I think, is to imagine a self free to ruin. Perhaps this is what Soren Kierkegaard meant by anxiety being the dizziness of freedom, the anxiety consequent on considering our possibilities. To advocate the absence of anxiety would then be to advocate the absence of this reckoning. Where a fine balance is maintained, our vices can serve us in the same way our virtues do.

It then becomes a question of degree with certain traditional vices [like anxiety, criticism, doubt, flagellation, desperation, envy—which Nietzsche’s works, particularly On The Genealogy of Morality, identifies as a means of acknowledging desire or the gap in one’s life—feelings of worthlessness and the inability to accept oneself—not a healthy process, I suppose!] to ensure they do not tilt the scales beyond counterbalance, beyond utility. And as the years pass, we adjust the scales.

Poet’s Dictionary

Knowing [adjective]

\ ˈnō-iŋ \

Definitions of knowing

1a : [can be] a limiting thing.

Etymology: English word knowing from the Old English cnāwan (earlier gecnāwan ) ‘recognize, identify’, of Germanic origin; an excerpt of Richard Hugo’s essay Writing off the Subject.

Readings

I read this brilliant novel by way of the insightful recommendation of a dear friend.

Nicole Dennis-Benn does wonders in her debut and I’m currently reading her sophomore, Patsy. The narrative explores the lives of Margot, her sister Thandi, her mother Delores and a community of others. The lives of these women are illuminated upon with an attentiveness that animates them as they encounter, explore or evade lack, loss, love, desperation, abuse, resentment, colourism, classism and religion-inspired homophobia to name a few. By dividing the book into three parts, she induces a rhythm that lends complexity to the dynamics between siblings—Margot and Thandi, Delores and Winston—mother and daughter—Delores and Margot, Merle and Delores—lovers—Margot and Verdene, Thandi and Charles.

misled* [Tears. And Nicole took a screenshot of this tweet, talk of a first impression.]

Nicole Dennis-Benn’s women are fully themselves, fully human, terribly so and for that, they are as memorable as they broke my heart.

As an appetizer or dessert, consider reading Sophie Mackintosh’s vivid and memorable short story, The Last Rite of the Body. which opens with an unsettling first sentence; and Joan Didion’s essential essay On Self-Respect.

“My ex-boyfriend dies, and we all gather to put our hands into his body.”

Sophie Mackintosh, The Last Rite of the Body.

Speaking of first sentences, here’s another.

“I would be lying if I said my mother’s misery has never given me pleasure.”

—Avni Doshi, Burnt Sugar.

Playlist

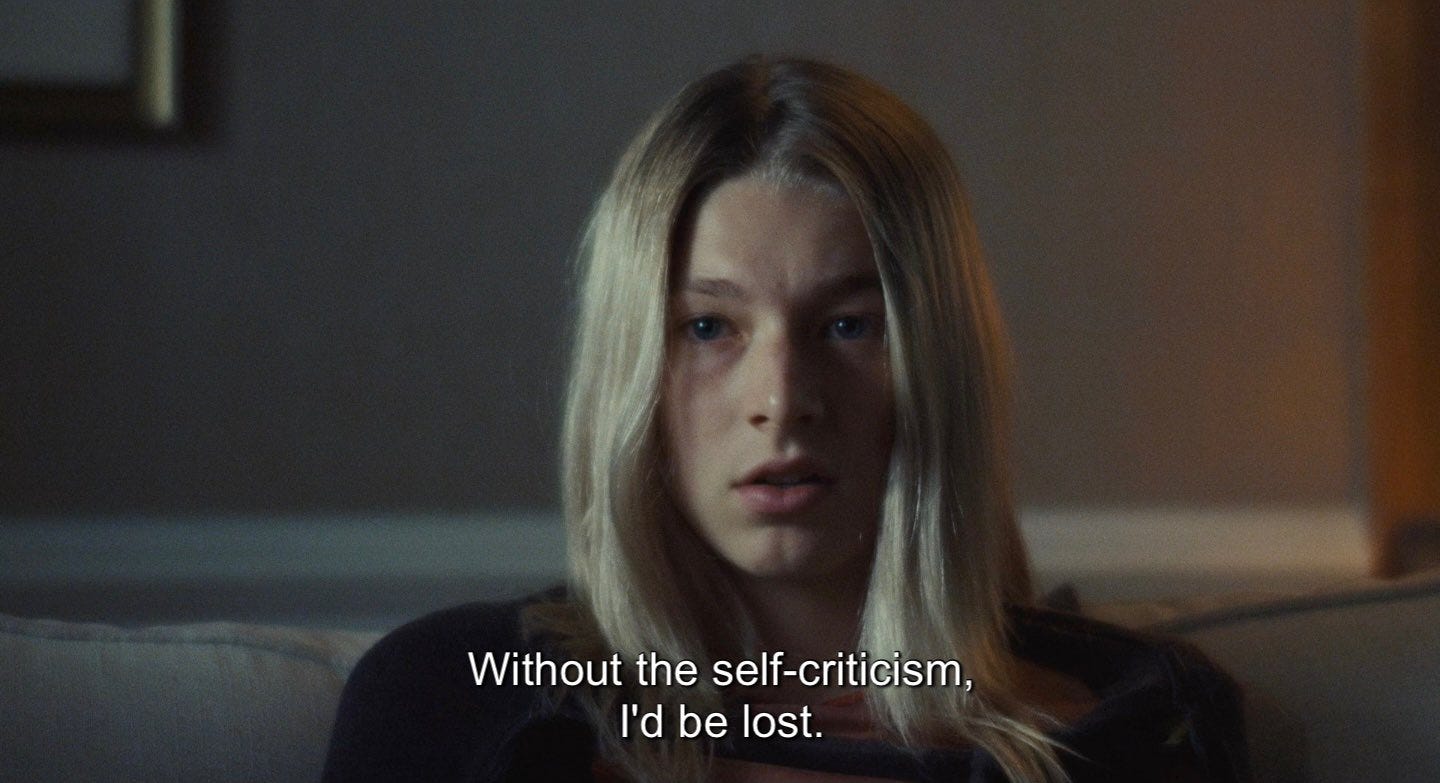

The gap between this letter and the last has seen several album releases across genres, and this year opened with a sophomore album—Caprisongs—from one of my favourites—FKA Twigs.

Enjoy listening to FKA Twigs’ meta angel, Tay Iwar’s Monica, BOJ, Falz and Ajebutter 22’s Too Many Women, Dave and Kamal’s Mercury, LADIPOE ft Amaarae’s Love Essential and others on this playlist curated for you.

Enjoy this video as well.

Kindly share this letter, leave a comment below or send a message if you’d like. I wish you a blissful year with balance in your scales.

Love,

Ọbáfẹ́mi