Answer truly, if only for a moment and to yourself: how are you in the home of your body?

I hope this little letter finds you well. It has been quite a quarter. Considering that stretch of time, I hope your plans have not been unruly. In my home, I am nurturing my rhythms, reading, relishing teas, experimenting and dreaming. I am well enough. Even on the days Labrinth & Zendaya’s I’m Tired plays on a loop.

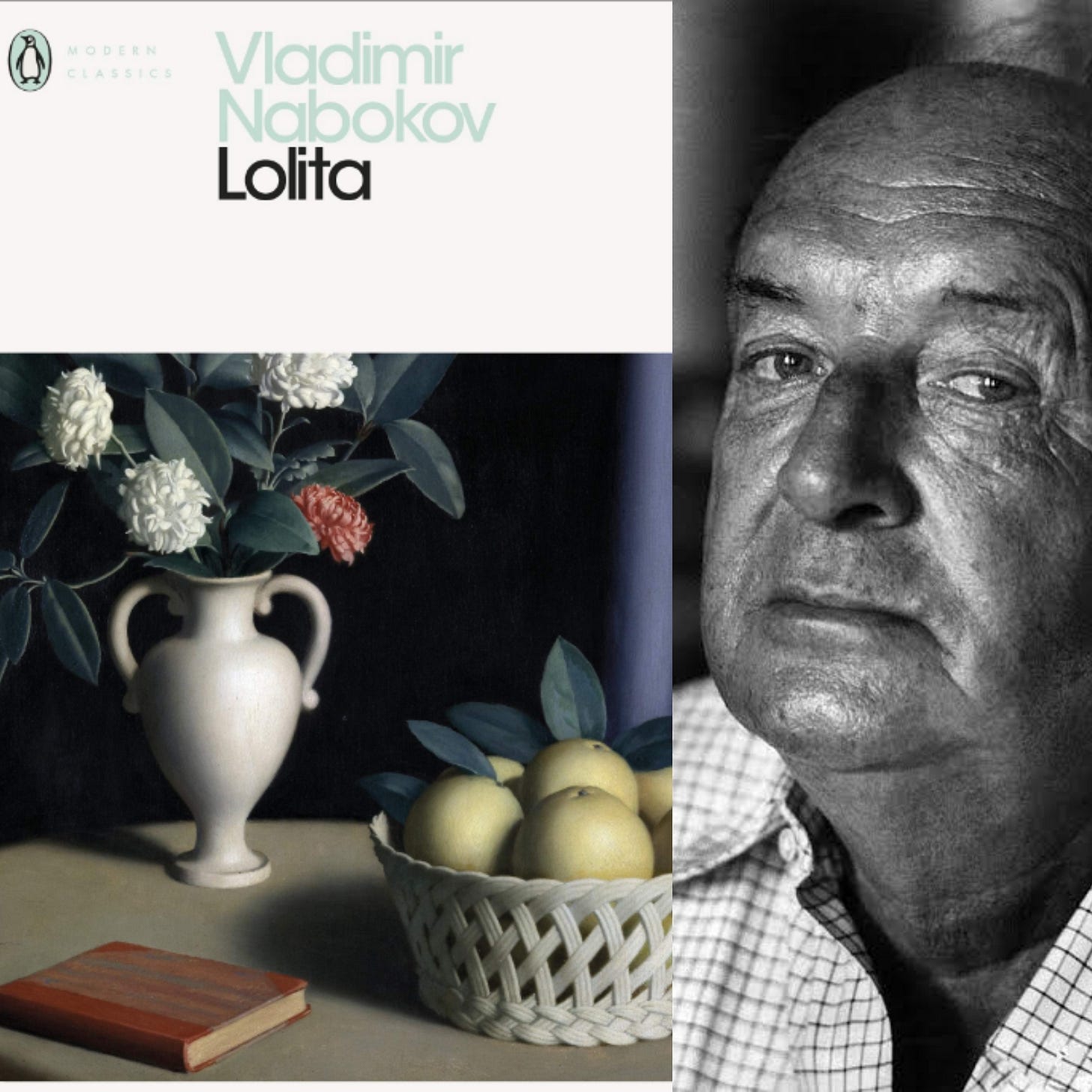

On Nymphets and Aesthetic Bliss

XXI

In the days leading up to this sentence, I read Lolita.

.

XXII

That I gave the former sentence its standalone section might strike you as dramatic, and I take no issue with that, if you’ve read the book. If you haven’t, you might want to delay your judgements.

The high opinions I now have of the book surprise me. It was inconceivable, in the beginning, that I could enjoy or even consider rereading it. I oscillated between so many feelings that by the middle of the book I was a thoroughly tired pendulum between disgust and admiration, shock and relief, laughter and sobriety, anticipation and repulsion; biding my time.

Speaking of time, it is ripe to say. The book is brilliant.

.

XXIII

“I remember being so young I thought all artists were good, kind, loving, exceptionally interesting, and exemplary human beings.”

—I Remember, I Remember by Mary Ruefle.

.

“One of the questions my students ask me, what do we do with Whitman? What do we do with all of these terrible men, right, in the canon? And I think, well, one of the worst things we can do is sweep them off the desk, because then we stop thinking about them. […] What’s more useful, I think, is that Walt Whitman radicalized the poetic American line according to the King James Bible at a time where America was falling apart, leading towards the Civil War. He was also racist. Those are simultaneous truths. And we honor ourselves by holding them and asking “why?” How did the thinking triumph and how did the thinking fail? And then we can decide for ourselves and do what Emerson said, in that reading is sifting for gold.”

—Ocean Vuong, in a conversation with Tommy Orange at City Arts & Lectures.

.

Remarks on the morality of Lolita abound, and most of them either emphasize its amorality or question its necessity—why did he have to write it? The possible answers to the why of art are varied and complex and perhaps a conversation for another day. But this wonder at the necessity of the book, or the certainty of its amorality, is one I can understand despite disagreeing. A similar understanding forms the impulse running through the book and makes it possible for Nabokov to flesh the character of Humbert.

I understand; because only a few times in my reading experience have I come this close to a feeling of moral danger. With each flip of the early pages, I felt inched towards a precipice—corruption lying in wait, the jaws of its abyss gleaming—and when the sense of danger eased, complicity gnawed at me every time I considered the language lush. [And the entire book is lush, but I am getting ahead of myself.] I felt this gnaw each time I appreciated Humbert’s poetic sensibilities or pretensions and every time he declared himself a poet—as a means of sublimating his actions or distinguishing himself from other criminals and “sex fiends” with less poetic motivations. An instance: “The gentle and dreamy regions through which I crept were the patrimonies of poets—not crime’s prowling ground.” With such remarks, I understand if you think fondly of Plato’s banishment of poets from his Republic.

The poetic sensibilities start early on, with references to Edgar Alan Poe’s Annabel Lee through characterization and language in the first chapter. The character of Annabel, who is a precursor to Lolita, is an apparent reference. Then the language mirrors fragments from the poem as “kingdom by the sea” becomes “princedom by the sea,” and the envy of angels that kills Annabel Lee becomes “what the seraphs […] noble-winged seraphs, envied.” Edgar Allan Poe recurs: “Oh Lolita, you are my girl, as Vee was Poe’s and Bea Dante’s […]” and Dante recurs: “After all, Dante fell madly in love with his Beatrice when she was nine, a sparkling girleen, painted and lovely, and bejeweled, in a crimson frock, and this was in 1274.” Seeking kinship with Dante through love and madness, Humbert suggests that in 1274 the poet was not also nine. And so sensibility slips its sober mask and pretension smiles. Then, as if taunting the reader with the duplicities to come, Humbert makes a distinction: “ “The orange blossom would have scarcely withered on the grave,” as a poet might have said. But I am no poet. I am only a very conscientious recorder.” Only for him to erase my illusive relief sixteen pages later with the remark: “Emphatically, no killers are we. Poets never kill.” I remember closing the book and calming myself with a disbelieving laugh, thinking, who is ‘we’ with this guy?

Thinking, if he were truly a poet, what do I make of his ore, what gleams beyond the gore?

Before further appreciating the language of Nabokov, a few thoughts on what eased my feeling of danger.

I realized I didn’t find the book amoral because it doesn’t pose a moral question. And I was glad to have this corroborated by Nabokov in his endnote On A Book Entitled Lolita, where he remarks, “… Lolita has no moral in tow. For me a work of fiction exists only insofar as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss, that is a sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm.”

The impulse that fleshes Nabokov’s Humbert pulses in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye through the character of Elihue Micah Whitcomb—or Soaphead Church. If there is a moral question in The Bluest Eye, it asks why Pecola Breedlove desires blue eyes. And while Morrison addresses this larger question through relationships and colourism and beauty hierarchies and race and violence and self-perception, the paedophilia of Soaphead is incidental. Incidental, because Morrison’s characterizations are notable for their lack of intrinsic narrative judgements—if you consider a Morrison character loathsome, the loath is yours. Incidental, because the book’s stand on the desire for blue eyes and the root of that desire is clear, and that clarity extends to the reader’s perception of Soaphead for his role in granting those eyes. Incidental, because you can count or discount his paedophilia as a motivation for his role in the question of Pecola’s blue eyes; the paedophilia that forbids him to “forget about the children” or “let them go wanting,” the paedophilia that makes him a creator worthy of God’s jealousy “I did what You did not, could not, would not do: I looked at that ugly little black girl, and I loved her. I played You.”

With a similar impulse to a different end, Nabokov’s Humbert preempts the moral judgements to his confessions by inviting the reader to his arraignment with his repeated calls of “Ladies and gentlemen of the Jury.” The book then does not pose a moral question because by its first chapter, typical moral concerns are resolved and the consequences of moral judgments are already at play. The moral responsibility of granting or withholding absolution does not lie with the reader. Lolita is free from him: “Oh, my Lolita, I have only words to play with!” We learn he is as “conscientious” a recorder as he is unreliable a narrator even when asks we “participate” in scenes with “impartial sympathy.” He despairs in the face of Aubrey McFate—the force of fate, which is, of course, Nabokov—who offers him “fantastic gifts” only to snatch them away. And with the resulting freedom from morality, Nabokov and the reader can interact with the rot of Humbert’s mind, the brocade of his mania and yearning, the depravity of his intentions, and most of all, language.

An instance of a pedophilic portrayal that poses and answers a moral question is in a segment of the 2013 film, Nymphomaniac Volume II. Outside this segment, the movie makes interesting connections between sex and religion, art, iconography, and fishing—yes, fishing, proving again the delicate interconnectedness of things. In the concerned segment, Joe has taken up a peculiar job that involves combining duresses to secure debt payments. One of her methods involves determining the debtor’s sexual deviations and threatening to make this information public.

So, if you are being owed money; there’s an idea.

The entire movie is a dialogue between her and Seligman, and subsequent shifts in dialogue or characters are portrayals of the events being described. With that in mind, the script for the concerned segment reads:

.

.

Joe [to Seligman]: But for once, here was a man I was unable to read sexually, so I became persistent.

Joe [to Thugs—or Helpers—1 and 2]: Tie him to the chair. Don't hurt him.

Joe [to Debtor Gentleman]: I can't find a stain on you, but my experience tells me that no man is spotless. Luckily, you're equipped with a very reliable truth detector. I'm going to tell you a few stories. All you have to do is listen. You're in a bar watching a couple...

Joe [to Seligman]: I now meticulously went through the catalogue of sexual deviations in fictional form. Stories about sado-masochism, fetishism, homosexuality, you name it. But he didn't react. And I'd almost given up when I said... On your way home, you walk through the park. And something makes you stop. You hear something. Yes, that's it. You can hear the children in the playground. You sit on a bench nearby and watch them play. There's a little boy in shorts. He's playing in the sandpit. He looks at you with his blue eyes. He smiles at you. I think he comes to you. He sits on your lap and looks up at your face. He says he'd like to come home with you. At home, you can't fight the idea of being naked together. He crawls all over you. You get an erection.

Debtor Gentleman: Won't you please stop?

Joe [to Debtor Gentleman]: He lies on his stomach. You pull down his pants.

Debtor Gentleman: I'll pay!

Seligman [to Joe]: You did what?

Joe [to Seligman]: I gave him a blowjob.

Seligman [to Joe]: Why? That pig!

Joe [to Seligman]: - I took pity on him.

Seligman [to Joe]: Pity?

Joe [to Seligman]: Yes. I had just destroyed his life. Nobody knew his secret, most probably not even himself. He sat there with the shame. I suppose I sucked him off as a kind of apology.

Seligman [to Joe]: That's unbelievable.

Joe [to Seligman]: No, listen to me. This is a man who'd succeeded in repressing his own desire, who had never before given into it, right up until I forced it out. He had lived a life full of denial and had never hurt a soul. I think that's laudable.

Seligman [to Joe]: No matter how much I try, I can't find anything laudable in pedophilia.

.

.

Now, on to aesthetic bliss.

.

XXIV

The duresses Joe uses in her debt collection brings to mind a coercion Humbert imagines: “I might blackmail—no, that is too strong a word—mauvemail big Haze into letting me consort with little Haze by gently threatening the poor doting Big Dove with desertion if she tried to bar me from playing with my legal stepdaughter.”

Mavuemail. How lush.

The choice of mauve is interesting for its dualistic meaning—the word can either signify a moderate or strong purple—its distinction of more subtle manipulations, its internal alliteration—producing a delightful oral experience with the lips pursed at m /m/, the mouth gaping slightly at a /əʊ/, the teeth teasing lips with the frictive sound of vue /v/, before mirroring the former syllable by pursing at m /m/, then gaping wider for the tongue to rise and nestle behind the upper incisors at ail /eɪl/—and its connection with style. The literary term Baroque connotes the prevalent European 17th Century approach to architecture and other art forms notable for its grandeur, tension, sensuous richness, stylistic complexity, emotional exuberance and blurred distinctions between genres and artforms. By extension, the term—which traces its etymology to the Spanish word barrueco or the Portuguese barroco for describing the beauty of an imperfectly shaped pearl—refers to writing that lends itself excessively to figurative language and ornate expressions. In literary criticism, this is also known as purple prose.

Mavuemail. Purpleprose.

In several humorous turns, Nabokov’s Humbert devotes language to the ironic naming of locations and characters. Humbert passes the night before a murder at “Insomnia Lodge.” He makes a connection between the words “therapist” and “the rapist.” He describes the “overdeveloped gluteal parts” of Mary Lore with the word “fundament,” which, of course, means what it sounds like, fundamental, as well as butt. The character of Quilty—Humbert’s mirror who he murders absurdly—rings close to guilty. Before Humbert murders Quilty, they have a winding conversation. Quilty offers to buy Humbert’s gun. Humbert reads Quilty a poem. Quilty provides his review and adds, as a playwright, the dramatic implications of their scenario. Humbert confides in the reader that Quilty’s French improves as their conversation winds, and when the gun “hurtles” under “a chest of drawers” they roll “all over the floor, in each other’s arms, like two huge helpless children.” In the end, Quilty dies “in a purple heap.”

Some of the reservations literary critics have against purple prose is its distraction from narrative. I beg, Nabokov writes, to differ. The reader learns from the poetic sensibilities and sublimations, the biblical allusions, the interspersing of French, the art appreciation that influences the description of Lolita’s “Botticellian pink” features and her sleep “as still as a painted girl-child,” and the self-awareness that enables a third-person narration of himself; the essence of Humbert’s character. The reader learns that monsters share the flesh of the virtuous. The Devil has no horns. Ask the Lord who listened to his honeyed hymns.

.

XXV

I edited some of these paragraphs during a church service, secluded, with Lolita in my lap. The book, of course.

I wonder where this stands, morally.

Playlist

Enjoy listening to Rema’s Runaway, Celeste’s To Love A Man, Labrinth & Zendaya’s I’m Tired, Sabrina Claudio’s cover of Olivia Rodrigo’s Favorite Crime, Nonso Amadi’s Foreigner, Aylø featuring MOJO’s Indo Smkn and BOJ, Kofi Jamar & Joey B’s Get Out The Way.

Be tender with yourself.

Love,

Ọbáfẹ́mi